Article on the State of Bolivia’s Mining Industry

Bolivia: A Blizzard of Misinformation on Mining and Everything Else

by: Christopher Ecclestone

October 12, 2008 | about stocks: CDE / PAAS / SIL / YPF

Evo’s bark is much worse than his bite.

- The media and foreign interests have conveniently lumped Evo Morales in with the politics of Hugo Chavez. In a world where the Morales government has few kindred spirits it has coalesced with the Venezuelan leader out of convenience rather than conviction

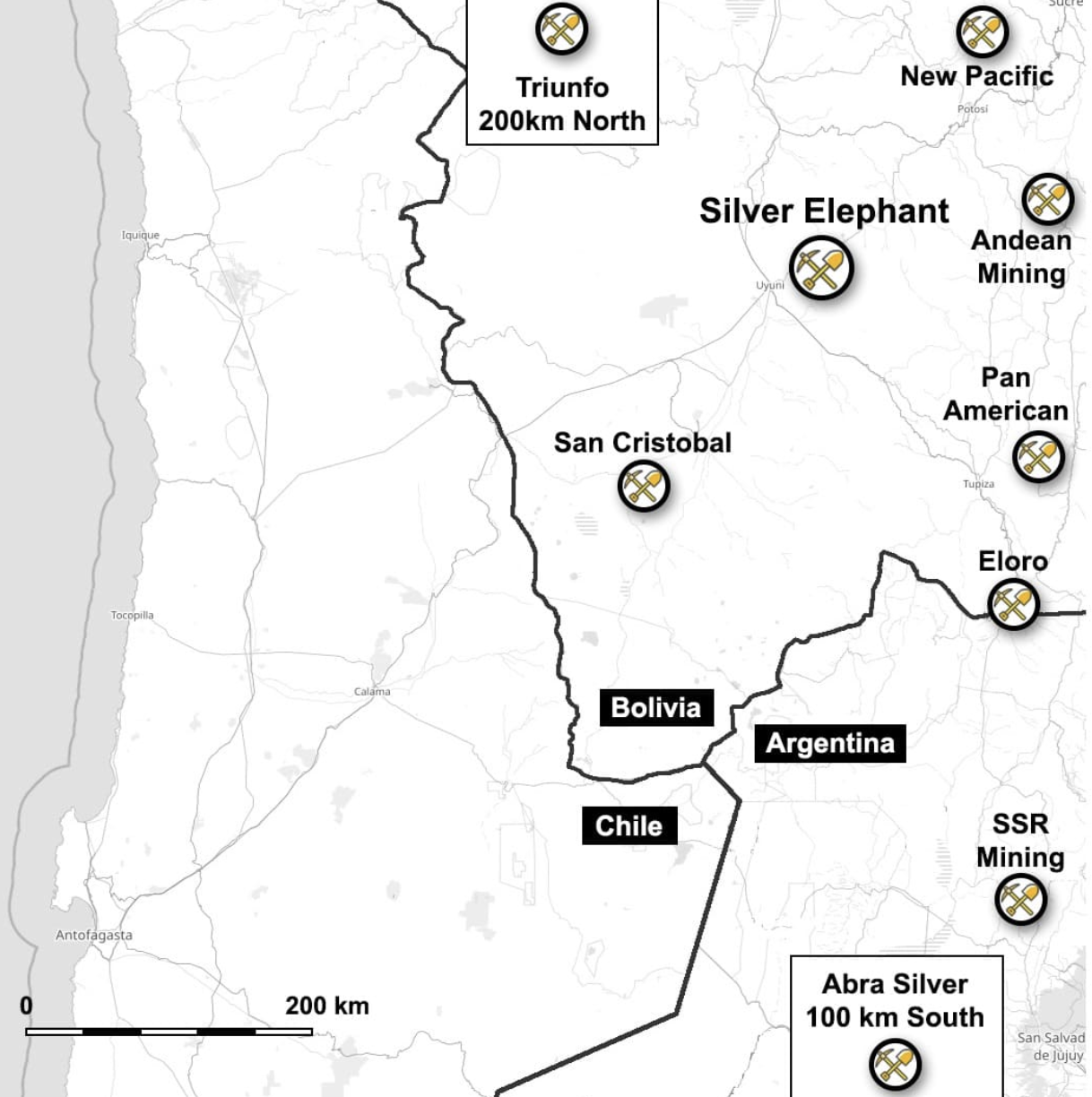

- Bolivia is fabulously wealthy and prospective on the mining front, having been for hundreds of years the very paradigm of a mining nation with its fabulous Potosi mine. A new era of exploration and production has begun.

- A handful of miners, including some international majors are forging ahead in Bolivia with minimal hassle.

- The HalfMoon provinces have been agitating for independence. This may yet be achieved, however, we would note that this would make the “upper” half of Bolivia even more dependent upon largescale mining for its financial survival. The resources or skillsets for “goitalone” in a nationalized context do not exist.

- The Morales government has an obsession with reversing the corrupt Comibol privatization, and rightly so, however its efforts are being painted in a negative light because Xstrata (XSRAF.PK) is the main party in the spotlight for having ended up with the wrong assets. This is more a reflection of Xstrata’s failures in due diligence than on the Morales’ government in our opinion.

- The Morales government is not the unsophisticated revolutionary regime that many would paint it. Peasants are renowned for their instinct at selfpreservation and bettering their interests, foreign investors should interpret the reports and actions in this light.

The Weight of History

This country was the epitome, for many decades, of the South American banana republic with serial military coups. While the country is not renowned for its bananas, it has had a long historic relationship with mining, chiefly through its mythic Potosi Mountain and its prodigious silver and tin mines. The coups were no joke though as the country averaged more than one per annum in the decades after the Second World War. Despite the image of blood in the streets that this conjures up, the Bolivian coupmongers were renowned for their relatively bloodless changeovers that tended to be internecine disputes between different military factions. The population consisted of an elite (largely pure blood European) perched on top of a generally apathetic and downtrodden native population of Aymara and Quechua Indians. Once again we might refer investors to Joseph Conrad’s seminal novel Nostromo for a depiction of elites and the masses interacting in a timeless Latin American fashion.

To add to the mix we have the disastrous war of the Pacific against Chile in which the Chileans (with British support) basically made a grab for Bolivia’s nitrate rich coastal province and succeeded in cutting Bolivia off from the sea. This still rankles and should not be forgotten in this mix. Then there was the bitter and largely unnoticed War of the Chaco between Bolivia and Paraguay over the oilrich flatlands in the 1930s. Curiously this ended up in popular literature by being parodied in the Herge bande dessinee, “Tintin & the Broken Ear”. This war was yet another debacle for Paraguay (a country even more historically trampled on than Bolivia). What it highlighted was the energy potential of the then thinly populated Bolivian flatlands.

Time has passed and the flatlands, more akin to Brazil’s Matto Grosso than to Bolivia’s traditional Altiplano, became populated with postWW2 immigrants (some reputedly of dubious war provenance) that developed the agricultural potential through vast haciendas/latifundias and later via the discovery of massive natural gas reserves. Santa Cruz de las Sierras became the heartland for this development.

Despite the torrid history of coups, Evo Morales, the pulloverwearing indigenous leader (with a wellknown history as a coca grower) was elected in December 2005 and has managed to hang onto power.

The Separatist Movement

Basically the separatist movement has as its core tenet the splitoff of the lowlands from the highlands. The departments of Tarija, Beni, Pando and Santa Cruz are sometimes known as the “half moon” due to the crescent shape of the departments when looked at together in the East of the country. The relatively lowdensity lowlands would thus get the natural gas and other resources in that territory and evolve their own new state. This plan is dressed up often as some sort of Quebeclike quasi independence but few are fooled by this intermediate stage in the evolution of the new nation (again Conradlike in its roots).

Such a new state would be quite wealthy. Its leaders claim it would be more efficient and more stable and that it wouldn’t have the deadweight of La Paz and the Altiplano communities. The theory goes that those in the mountains would be able to exploit the massive mineral resources of the highlands. That the uplanders may not choose to do so is their problem.

Nothing New

Some have made out that the latest push (putsch?) is a racist reaction to the Evo Morales regime. This is a historical error. We first heard of the Santa Cruz independence movement back in the mid1990s when Evo was still weeding his coca plants and the white oligarchs were firmly entrenched in their mediocrity in the lofty heights of La Paz. The basic rationale behind the split is to create a new state, with new thinking, without the baggage of hundreds of years of rancour and class struggle that has been a large component in the torpor that the country has long suffered.

Brazil

When it comes down to it, Brazil will do what suits Brazil. Lula de Silva has made the right noises of solidarity with the Morales government but…what really suits Brazil? Well, when it comes down to it, Brazil desperately needs Bolivia’s natural gas. Bolivia has it but also wants to sell it to Chile and Argentina to keep in the good graces of those countries. We might also note that Petrobras was one of the companies expropriated of their natgas assets in the first actions of the new Evo Morales regime. If the Santa Cruz state was created, with the Brazilian hidden hand, then Brazil could move to the front of the line. Is Lula speaking with forked tongue? We think not. But are there other, more powerful and influential forces in Brazil than Lula? You bet!

Beyond the gas issue, there is iron ore. The El Mutun iron ore deposit in Bolivia (on the Brazilian border) makes Vale’s (RIO) assets pale into insignificance with an estimated 40.2 billion metric tons of iron ore. This site was initially being developed by EBX (MMX) of Brazil and was shut down by Morales on environmental grounds. Local protesters seized three Bolivian ministers and held them hostage demanding the site reopen. Now how’s that for a turnabout in the old story of hostile locals!

Currently this asset is in the lackluster hands of the Indian company Jindal, who have not moved the ball forward much. The investment required to produce a mine that might have output of 20 billion tons would cost $2.1bn by a recent estimate in LatinFinance. In the short term Jindal will invest $300mn on buildout annually from 2008 through until 2012 when production should be two million tons per annum. Full production of 18 millions tonnes per annum of pellets, rods and directly reduced iron could be achieved by 2014/5. Whether such ambitions or realized or not is another matter if Bolivia remains in the bad books of financiers (justifiably or not). Nevertheless even a scaled down El Mutun has the potential to right royally derail Vale from its ambitions to be the pricesetter in iron ore markets. A change of control to Santa Cruz could position Vale to move on the asset and neutralize it potential to “disrupt markets”.

Moreover what is currently the State of Acre in Brazil was persuaded to secede from Bolivia in 1903 and the Brazilians launched a war against Bolivia to hasten the process. Do not write off that ultimately Brazil might passively, if not actively, encourage the HalfMoon States to go their own way.

The US

Alas, as usual the US has not been too subtle in its actions in the region with the effect that it has driven some of its allies to stand with Evo Morales against the separatists and brought Hugo Chavez into the mix. The main event so far has been the expulsion of the US ambassador after he held clandestine talks with Reuben Costas, the separatist governor of Santa Cruz. It is not too clear what the US agenda here is. Unlike Brazil (or other neighbours) it doesn’t have a stake in the energy tussle. Is it that Evo is a friend of Hugo? Sure he is, but Morales has barely inched down the nationalization path that Chavez has forged and no US assets we have heard of have been threatened. Morales has not made aggressive noises towards neighbours, indeed, he has made more progress with Chile (the US “friend” in the area) than anyone else in 120 years. Its main danger here, whichever way the game plays out, is that the US will weaken its main priority (or what should be its main priority) the eradication of the flow of cocaine into the US.

The Referendum

In response to the pressures building the Morales government decided to take the issue to the people. In a referendum held on August 14th, 2008, the government won resounding support (more than two thirds of voters 67.4%) with only some reporting districts in the far north and west going with the opposition proposal. The final results by district are shown in the map to the left.

The results set off a wave of violence as the separatists grappled with what was quite clearly a big psychological setback for their campaign. If they had dominated all the flatlands they may have grounds to claim unanimous support for separation in those zones. But the map shows they did not. It is made harder to interpret these visuals by the fact that some of these “departments” are sparsely populated while others are dense. The more sparse areas are where the indigenous population predominates while the urban areas have more of the criollos inclined towards the separation concept.

The Mining Scene

Evo Morales has scared the living daylights out of the international press who have passed their fears onto the investment community. The fact that he was “indigenous”, which seemed to imply troglodyte to the wider world, is somewhat of a red herring. We could say that Evo’s former career as a coca leaf grower makes him not only exportoriented but also a commodity producer!

On a more serious note the chief “retrograde” step that he made from the capitalist perspective was his renationalisation of the oil & gas assets that were stripped from YPFBolivia (YPF) in the 1990s and sold off for a song at the instigation of our old buddies the IMF (remember them?). Ironically these assets are now the root cause of the dramatic improvement in the fiscal situation as neighbours like Chile, Argentina and Brazil vie (well, more like catfight) for Bolivia’s natgas exports. The further irony (akin to Ecuador) is that the nationalization has been a good thing for the holders of the country’s sovereign debt as it has improved the credit standing and ensured the ongoing cashflow to meet interest and principal payments.

The nationalization has been extrapolated onto the mining sector. He has not helped by using the “n” word when appealing to the cheap seats at rallies. Bolivia of course is one of the mining nations par excellence with the word “Bolivia” being almost synonymous with tin and historically linked with massive silver mining at the legendary Potosi mine. Despite the bad press, mining by foreigners bubbles along in Bolivia with the most prominent exponent being Apex Silver (SIL), which seems to have found a niche in the heart of Evo.

The last serious nationalization talk relating to mining was back early 2007, which leads us to think that he has put the plan on the backburner. YPFB was the real prize. A collection of putative mining projects owned by foreigners would be most likely to remain on the drawing board particularly if taken over by the slowmoving Comibol (the State mining enterprise) where the metals prices on their website have not been updated since early May! Shakespeare would venture that nationalization “should be made of sterner stuff”.

Comibol: Back from the dead?

The State mining giant, Comibol (Corporación Minera de Bolivia) had its feathers plucked when it was subject to privatization the late 1990s. This still grates in Morales circles and considerable effort has been put into turning the process around. Investors should not confuse however, a revived Comibol initiative as a threat to projects that never were within the ambit of the preprivatisation entity. The first stone was cast when on 7th of February, 2007, the cabinet approved Supreme Decree 29026, returning the ownership of Glencore’s Vinto foundry to the state. Two days later the government sent troops into the Vinto metallurgical complex, to take the country’s main foundry back into public ownership.

The then Mining Minister Guillermo Dalence said that there would be no compensation to Glencore of Switzerland, Vinto’s owners since 2004 since the government was taking back state property which had been illegally transferred to the private sector. The government promised to respect jobs at the foundry and invest US$10 million in it. Vinto began operations in 1971 as part of the state metallurgical company ENAF (Empresa Nacional de Fundiciones). Bolivia thus began to earn more by processing its minerals locally instead of sending metal concentrates abroad.

Although Vinto is primed to cast different metals, such as antimony, it has principally been used for preparing tin ingots for export. It is currently operating at about half its installed capacity (12,000 of a possible 20,000 fine metric tons a year). Though estimates vary widely, it was valued in the 1990s at between US$54 and US$140 million.

The mining sector was not privatised during the first waves of adjustment in 1985 and the mid1990’s. Instead it was sold off during the Banzer government (19972001). Our old buddies at the IMF liked playing midwife at such births. The privatization at an earlier date would have been difficult anyway due both to resistance from the workers and the very low prices of most minerals, particularly tin, throughout this period (198595). The history of Vinto is worth telling as it highlights why the initial transaction still sticks in the craw of the Morales team and why Glencore’s seizure of the high ground may only go to show that quicksand can exist on moral high ground as well.

In December 1999, Vinto was privatised and sold to an AngloIndian firm, Allied Deals (which also bought the tin mine Huanuni). Allied Deals bought the complex for US$14.7 million from the Bolivian state, at a time when its immediate assets had been valued at US$16 million. This firm passed its holdings to RBG, another UKbased company, which then went bankrupt. Vinto ended up in the hands of the liquidating auditors, Grant Thornton. According to the original agreement, Huanuni and Vinto should then have returned to state administration through COMIBOL. In fact, Vinto was sold in 2002 to COMSUR, the mining company owned (since 1962) by the newly elected Sánchez de Lozada’s. Some press reports say that COMSUR paid Grant Thornton US$6 million for the foundry. Glencore International, which acquired Vinto in January 2004 as part of a package Sánchez de Lozada sold off after being forced to leave the presidency.

The Morales’ government’s argument is that the 1999 sale was illegal and that Congress never approved the contract. In some opinions the state lost out badly, since the amount Allied Deals (what a name!) paid did not reflect the foundry’s real value of around US$140 million. The government claims that Glencore has made no subsequent investment. Nor has it carried out any major maintenance with two of the big foundry ovens lying unused, and the antimony oven being no longer operational.

Of course 1999 was a long time ago and tin was in the dumpster for ages. The value of Vinto nowadays can be said to be much higher due to tin’s stellar rise. Hindsight is 20/20. As the chart above shows tin hit nearly US$26,000 in May of this year its highest level since at least 1980. Price rises were due to strong world demand for tin, boosted by strong demand in China and India, combined with the fact that Bolivia’s main competitors: Malaysia and Indonesia, no longer produce ingots but products of higher value.

Most recent owner is Glencore International (via its local subsidiary Sinchi Wayra). After GlencoreSinchi Wayra bought up COMSUR from Sanchez de Lozada, they inherited Vinto as part of the package. Other properties acquired by them at the same time included three important mines, Bolívar, Colquiri and Porco. These were operated in either joint ventures or leasing agreements with COMIBOL. According to the local newspaper La Prensa, Glencore/ Sinchi Wayra was Bolivia’s largest mineral exporter in 2006. It exported minerals (zinc, silver, lead & tin) to the value of US$503 million, representing 60% of all the

Evo still continues to sharpen his knife for the former Sanchez de Losada administration. At the time of the Vinto seizure Morales also warned that other mines belonging to former president Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada would also be re nationalised. Sanchez de Losada now resides in Chevy Chase, Maryland.

PanAmerican Silver (PAAS)

The San Vicente silverzinc underground mine is Pan American Silver Corp.’s only mining interest in Bolivia. More than 20 bonanza type silverzinc veins are known to occur over an area of 1.5 kilometres on surface and extend to at least 200 metres in depth. The project consists of 15 mining concessions totaling 8,159 hectares.

There has been sporadic mining activity at San Vicente since colonial times. The current property was operated by COMIBOL, the Bolivian state mining company, from 1972 until 1993 when mining was suspended, pending privatization. Pan American Silver optioned the San Vicente project from COMIBOL in 1999 and became operator, advancing the project through drilling, underground sampling and metallurgical test work.

In late 2001 Pan American Silver and COMIBOL entered into a twoyear toll milling agreement with EMUSA, a wellestablished Bolivian mining company, to process up to 250 tonnes per day of San Vicente’s ore at EMUSA’s nearby Chilcobija mill. This arrangement generated sufficient revenue to offset the property’s holding costs and generated valuable information on the mining and milling characteristics of San Vicente’s ore. In early 2006 Pan American Silver signed a jointventure agreement that granted EMUSA a 40% interest in the project. In mid2006, Pan American Silver entered into another toll milling arrangement with EMUSA to continue processing at its mill.

In 2007, Pan American Silver acquired EMUSA’s 40% interest, increasing ownership of San Vicente from 55% to 95%. We have no opinion/rating on PAAS.

Apex Silver (SIL)

This company has been synonymous in recent years, for better or worse, with the fortunes of miners wanting to do business in Bolivia. It is a mining exploration and development company with its flagship asset being the 65%owned San Cristobal silver zinclead project, located in the Potosi district of southwestern Bolivia. The other partner is Sumitomo (SSUMY.PK). San Cristobal is one of the world’s largest openpit silver deposits. It hosts an ore body that contains approximately 450 million ounces of silver, eight billion pounds of zinc and three billion pounds of lead in proven and probable reserves. The main ore body remains “open” both laterally and to depth with numerous satellite targets existing within the San Cristobal district.

The mine is still in rampup mode. The concentrator throughput for the second quarter averaged 34,000 tonnes per day, approximately 85% of the 40,000 tonnes per day design capacity. The key focus is now on the final ramp up to full capacity and achievements in metals recovery. Production from San Cristobal in 2Q08 totaled approximately 84,000 tonnes of zinc concentrate and 23,000 tonnes of lead concentrate, containing approximately 4.2 million ounces of payable silver, 42,000 tonnes of payable zinc and 15,000 tonnes of payable lead. This produced revenues of $60 million for the quarter. Concentrates sold contained approximately 1.6 million ounces of payable silver, 26,500 tonnes of payable zinc and 5,400 tonnes of payable lead. The company received an additional $53 million in the second quarter for concentrates shipped in the second quarter, which was recorded as deferred revenue.

Income from operations totaled $204 mn, including a massive gain on metal derivative positions. This was a $223 million mark to market gain related to its metal derivative positions, which is primarily the result of declining lead and zinc prices during the period. Without this though, we would note, the earnings would have been negative. As a result of the interesting cash situation that the company finds itself in it recently did a discounted sale to Sumitomo of the payment flows in exchange for $70mn.

Net income for the quarter was $178 million, or $2.57 per diluted share, including the gain on metal derivative positions and a gain of $63 million related to the sale of the deferred payment right to Sumitomo. As we can note here Apex is doing well on the production front but not on the profits front. The shift to full production should help but the silver plunge should not. Certainly though it would be a stretch to attribute its financial travails to Evo Morales, though some might try.

While this note is primarily aimed at overviewing projects and ascertaining their political vulnerability, it might be worth looking at Apex’s hedging as investors from a distance tend to grab at headlines rather than looking at specifics. Apex being the bellwether is prone to be misinterpreted. The company has been somewhat cagey on its hedging activities. From what we can gather from anecdotal evidence Apex has hedged more than half its zinc and nearly all its lead production through 2011 at prices of $0.48 for zinc and $0.29 for lead. A small amount of silver has supposedly been hedged at $7.30 but knowing the company’s tendency to hedge we would not be surprise to hear they had taken advantage of the price soaring above $20 earlier this year to put some more on.

These hedges have a rocky history in FY06 they produced a loss of $715.1 million, while for the year ended December 31, 2007, the company recorded a gain related to its metals derivative positions in the amount of $19.3 million. The latest gains have been from writing back some of these earlier paper losses. We presume this is largely from the perspicacious bet on zinc prices. The company is confessing exactly where the losses and gains are from and how they net out. In any case, no one can blame Evo for them! Until the company is more upfront on this score, the main risk here is negative surprises. We rate the company as an Avoid for now.

South American Silver [TSE:SAC]

This new name on the landscape is a mineral exploration company that acquires, explores and develops mineral properties, primarily silver, gold and copper in South America. We recently got to meet the company and walk through their strategy and the dynamics of mining in Bolivia at the current time. This was the spur to write this review of the Bolivian scene. The company was a spinout of the nonNorth American assets of General Minerals and presently holds stakes in three properties: the flagship Malku Khota silver/indium/gold and the Laurani gold/silver properties in Bolivia and the Escalones coppergold molybdenum property in Chile.

The most relevant for investors at this time is the sizeable Malku Khota project, which came in this week with a NI 43101 Indicated Resource of 144,597,000 oz of Silver and 845,000 kg of Indium and an Inferred Resource of 177,783,000 oz of silver and 968,000 kg of indium. While silver is in the doghouse at the current time, indium is a metal being bandied about the sexy new thing. If SAC can get this open cut mine going then it has the potential to be producing up to one quarter of the world’s Indium which is a primary component in LCD screens, most notably the flavour du jour, large screen TVs. While financing for any project is tight at the current time, the obvious course here is to get an enduser to either buy forward the production or to take a large minority stake in the mine to kickstart it to production. Fortunately for SAC, the project is scaleable with a small or large startup being a choice available to the company.

The company has management that has been working in Bolivia for decades now and is wellattuned to the local conditions. As such, it has been putting a lot of effort into charming local communities to get them on board with the project and avoid some of the pitfalls others have fallen into (or brought upon themselves).

Even more attractive is the fact that the company has a market cap of a mere $12mn and 20 cts of its 25 ct share price is composed of cash. It would appear to us that SAC is a Speculative Buy at this point. Any news on a forward sale of its Indium production would hike this into the Strong Buy category, but it is too early to pin too many hopes on that coming through.

Apogee Minerals [CVE:APE]

Apogee Minerals has two assets. One is exclusively its own and one is in partnership with the aforementioned Apex Silver. The prime project is the La Solucion Mine which produces approximately 2,300 tonnes of ore each month averaging 44g silver/t, 1.3% lead and 4.11 % zinc (2006 average), has a 17 year production history and hosts a 120 tonne per day flotation mill.

On February 19, 2007, Apogee announced a NI 43101 Inferred Mineral Resource of 18.4 million tonnes of 43 g silver/t, 1.16% zinc, and 0.68% lead, or a silver equivalent grade of 181 g/t silver using metal prices of $US 10.43/oz silver, $US 1.30/lb zinc, and $US 0.55/lb lead. Then in April 2007, it announced some further results at a nearby zone. The object is to prove up sufficient reserves to justify expansion of the currently limited production with a goal of creating greater efficiencies on higher throughout. However since then, no other action has been taken (or at least announced to have been taken).

Instead focus shifted to the company’s JV with Apex Silver over the PulacayoPaca project and has an ongoing program of exploration with the objective of defining reserves at both Pulacayo and Paca, based on the mineralized intercepts obtained by Apex Silver. This is being done via infill drilling and modeling of these mineralized zones, metallurgical testing, etc.

The Pulacayo silver mine ranks historically as the second largest silver mine in Bolivia after Cerro Rico de Potosi. It was discovered in 1883 and since then has produced about 678 million ounces of silver, 200,000 tons of zinc and 200,000 tons of lead. In 1891 silver production reached 170,097 kgs (5.7 million ounces) and in 1923 the mine was flooded. It was subsequently dewatered in 1927 when Mauricio Hochschild took over the mine. After 1930 production increased considerably again and in 1951 concentrates were exported containing 68,843 kgs silver (2.3 million ounces), 18,652 tons of zinc, 3,191 tons of lead, 1,120 tons of copper and 15 kgs gold (500 ounces). In 1952 the mine was nationalized and exploited by Comibol. It was closed in 1958 when the average content of the ore was 10.5% Zn, 1.5% Pb, 0.9% Cu and 250 g/t Ag. These numbers indicate that the mine was more a victim of poor prices and low investment than exhausted reserves or low grades.

Production came mainly from the exceedingly rich and nonoutcropping Tajo vein system that was exploited down to a depth of over 1,000 meters. These veins split at shallow depths into a dense zone of veins and veinlets with stockworks and local disseminations, still containing according to Sergeomin in excess of 10 million tonnes grading 2.6% Zn, 1.3% Pb and 96 g/t Ag. In addition, Sergeomin state that silver lead and zinc could be extracted at low cost from the enormous waste dumps and tailings.

The Paca dome outcrops some four kilometers to the north of Pulacayo. The mineralization at the Paca dome is associated with siliceous volcanic breccias, where it forms steeply dipping bodies and adjacent volcanosedimentary units, where it is hosted in near surface shallowly dipping mantos. The main Tajo vein system at Pulacayo and the mineralization associated with the Paca dome were drilled by Apex Silver in the late 1990’s. Apogee has some interesting assets but we would prefer that it focused on increasing production. Production would pay for more exploration elsewhere. For the moment we would prefer to pursue other possibilities and maintain a Neutral rating on the stock.

The company is part of the same corporate grouping as Castilian Resources, which we have written on in the recent past. This sister company has in its portfolio the Achachucani project (formerly known as Pederson) through an option agreement where Castillian may earn up to a 90% interest. The site is located in Central West Bolivia approximately 350km south of La Paz and consists of an epithermal gold (2.3 Moz gold) deposit. This does not have a NI43101 on it.

The gold deposit has been subject to extensive exploration, including 21,616 meters of drilling (121 reverse circulation holes – 19,863 meters and 10 diamond core holes – 1,753 meters). Historical exploration, which was undertaken primarily by Orvana Minerals Corporation and BHP, defined an area of continuous mineralization for which a historical resource estimate of 51.6 Mt grading 1.4 g/t Au was delineated. Currently however the project is in a state of force majeure, according to the company, due to the opposition from local landholders.

Coeur D’Alene (CDE)

Buried amongst the farflung portfolio of Coeur is the San Bartolome project, which the company claims to be the largest new primary silver mine to be built in the Americas in decades. The facilities are located near established industrial infrastructure in the historically silverrich area of Potosí, where more than two billion ounces of silver have been mined. The building of the mine generated as many as 1,000 local jobs during construction, and employs approximately 200 now that it is in operation.

Total proven and probable reserves of more that 150 million ounces of silver are contained in surface gravel deposits, which lend themselves to simple, lowtech surfacemining techniques. Of the several deposits that are controlled by Coeur and surround Cerro Rico mountain, three are of primary importance and are known as Huacajchi, Diablo (consisting of Diablo Norte, and Diablo Este) and Santa Rita.

The San Bartolome silver mine started production early in 2008 and has been on a steep ramp up curve. The company advised around one month ago that daily silver production had steadily increased up to a level of 15,000 ounces per day, which was expected to result in approximately 500,000 ounces of silver production during the month of September. Through the end of August, San Bartolome produced approximately 390,000 ounces of silver yeartodate. CDE expects the operation to achieve full capacity in the fourth quarter. For the year, Coeur anticipates the mine will produce 3.2 million ounces of silver and that it will achieve its 2009 production estimate of approximately 9 million silver ounces. Once again this does not sound like an Evo induced disaster area.

As part of its efforts to reduce the chances of local opposition the company has established a foundation, called Fundespo, to assist in the development of new local industries, such as silversmithing and tourism. We have no opinion/rating on CDE.

Conclusion

It might sound like a pejorative but Evo Morales is a cunning peasant, and like any cunning peasant he knows to test the gold sovereign that the lord of the manor tries to pass off in the marketplace by biting on it. This is key to remember. The West is acting as if some of the local caudillos appearing in the Latin backwoods came from the same French university that spewed forth Ho Chi Minh or Pol Pot. The reality is that these are not disaffected sons of the urban middle classes but rather true peasants, who know the backwoods because they have been living in them for so long.

Peasants are renowned for being brutish, but also cunning. After being stomped on by Cossacks (or in the Bolivian and Ecuadorian cases by Conquistadores) for generations, only the smartest survived. Their taste in bowler hats may link them to the City of London of days gone by, but more than likely they keep the dollars gleaned at the market up there (incidentally the founder of Goldman Sachs walked around downtown Manhattan with letters of credit in his top hat…a peasant of a different age).

Evo could see when Bolivia was getting ripped. It wasn’t just Bolivia that had the galumphing hordes of Repsol trying to pull a fast one, with even the vivo Argentines being taken to the cleaners by the neoConquistadores. Taking back YPF Bolivia’s assets from those that had made off with them, has now tainted the Western perceptions of the Morales’ government towards all natural resource assets. This is an error. Then there is the association with the vilified Hugo Chavez. In reality there are probably as many photo ops of Lula with Hugo as there are of Evo with Hugo, it’s just that Lula is Wall Street’s darling and Evo is in a place Wall Street scarcely knows existed and useful scapegoat.

Most of the time the relevant parts of the Morales team are fully on board with foreign miners operating in the country and can’t wait to be seen at a ribboncutting ceremony. If this is the sign of an antimining administration then it is a stark contrast to the openly hostile approach of the Venezuelan administration with which the Morales regime is frequently relegated. Bolivia is case of “do as I do, not as I say”. Evo Morales can say anything he likes to the cheap seats and it works at getting him reelected and through hairy political situations. If there is one populace in Latin America (and we included Chile in the pool) that understands the importance of mining to putting the daily bread on the table, it is Bolivia. Man does not live by llamas and coca leaves alone!

Disclosure: No position, long or short, in any of these stocks.